Overview

Equity-oriented health policies honour the right to health (and related rights) of all people by creating and sustaining conditions for all people to achieve their highest attainable standard of health. Policy measures, whether within or beyond the purview of the health system, should be informed by evidence. The use of evidence to inform policy-making, however, requires that the data are provided in the right format, to the right person, at the right time.

Equity-oriented policy-making is the bedrock of the global development agenda, reflected in the mandate of WHO – which states that “governments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures” (1) – and the imperative of “leaving no one behind” in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2). Health equity is a policy directive around which there is global consensus and commitment, and obligation on the part of national and subnational authorities.

This chapter focuses on policy-making environments, where advancing action to reduce health inequities requires prioritization, allocation of resources, and design of policies or interventions, often in resource-scarce areas. Various forms of evidence, including inequality analyses, can help to inform these actions (see Chapter 24), taking into account other contextual economic, political, moral and practical considerations. The goal of Health for All is aligned with equity-oriented policy – and both the process and the outcome of equity-oriented policy-making must be transparent and accountable and result from robust ethical consideration.

The objective of this chapter is to introduce considerations, contexts and approaches for equity-oriented policy-making. After outlining general considerations for policy-making, the chapter describes primary health care and universal health coverage as guiding principles for equity-oriented policy-making, highlighting the concept of progressive universalism, in which populations experiencing disadvantage are prioritized on the pathway to achieving the goal of universalism. The chapter introduces the priority public health conditions analysis framework and its application as a holistic approach underpinning policy-making processes.

General considerations for policy-making

Setting a policy agenda for health equity raises several issues (3). In prioritizing policy actions, consideration is required regarding which inequalities constitute inequitable differences and are potentially subject to remediable actions; which subgroups warrant more attention or resources (e.g. due to disproportionate need or historical injustices); and how resources should be invested to balance improvements in overall population health with targeted approaches that focus on priority subgroups (4). Policy-makers may inevitably face competing demands and interests and will need to negotiate the extent to which policies and subsequent investments address equity concerns (5, 6).

To promote effective and impactful engagement in the policy process, it is important to align with national planning and policy cycles, including budget planning to secure financial resources for policy directives (see Chapter 4). National policy cycles are country-specific. Some countries have longer, overarching national health policies spanning multiple years, with other longer-range policies addressing specific health topics or priority populations. Countries may have scheduled annual reviews and updates, with different arrangements for working with international partners (7).

Health inequities reflect social and political circumstances that systematically disadvantage certain subgroups. Health system policies can help to reduce inequalities, but equity-oriented interventions operating outside the health sector entirely can also have important impacts (8). Policy action at several levels, including actions on proximal, intermediate and distal determinants of health, are vital to address the drivers of inequality. The importance of multisectoral actions aimed at social determinants of health (see Chapter 9) and efforts to improve societal-level injustices (see Chapter 10) are widely acknowledged – although in practice, policies and interventions often focus on individual-level behaviours, which may limit their effectiveness in the long term (9).

Policy environments for advancing Health for All

Equity-oriented health policies are instantiated in the Health for All goal, which builds a moral case for health equity. Health for All – whereby all people have good health for a fulfilling life in a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world – has remained a guiding vision for public health initiatives and policies around the globe since the late 1970s (Box 8.1). Health for All is emphasized in the WHO Fourteenth General Programme of Work for 2025–2028, which reaffirms WHO commitment to health equity and the common goal of promoting, providing and protecting health (14).

BOX 8.1. Health for All

In 1977, the 30th World Health Assembly resolved that “the main social target of governments and WHO in the coming decades should be the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life” (10).

In 1978, Health for All was adopted as a goal at the International Conference on Primary Health Care in Alma-Ata (now Almaty, Kazakhstan). The Declaration of Alma-Ata was a commitment among health leaders to advance primary health care and uphold values of social justice, health equity and the social determinants of health (11). It positioned health at the centre of development policy, shifting the onus of governments from providing health services towards being accountable for the health of their populations (12). The Declaration called attention to inequalities, stating that “the existing gross inequality in the health status of the people particularly between developed and developing countries as well as within countries is politically, socially and economically unacceptable and is, therefore, of common concern to all countries” (11).

In commemoration of the 40-year anniversary of the Alma-Ata Declaration, the Astana Declaration, endorsed at the 2018 Global Conference on Primary Health Care in Astana, Kazakhstan, renewed a commitment to achieve Health for All, involving major investments in primary health care to improve health outcomes (13).

Health for All conveys the WHO holistic understanding of health, which extends beyond the absence of disease and infirmity to broader aspects of physical, mental and social well-being that enable a fulfilling life. It captures the central importance of the surrounding environments, alluding to the diverse conditions that together are a prerequisite for population-level health. Aspiring towards Health for All upholds values of universality, community participation and social justice, respecting the significance of each person and their fundamental human right to health (15).

Under the vision of Health for All, individuals and communities live in environments that enable, protect and maintain health – and, when needed, have access to high-quality health services so they can take care of their own health and that of their families. Skilled health workers provide good-quality, person-centred care, and policy-makers are committed to investing in a full range of good-quality health services that are accessible to people, when and where they are needed. The pursuit of Health for All entails coordinated action across multiple sectors. A primary health-care approach for achieving universal health coverage is the means through which Health for All can be realized (15).

Primary health care

Primary health care is a whole-of-society approach to health that aims to maximize the level and equitable distribution of health and well-being. It focuses on people’s needs and preferences as early as possible along the continuum from health promotion and disease prevention to treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care. Primary health care encompasses three mutually dependent components: primary care and essential public health functions at the core of all integrated health services; multisectoral policy and action; and individual empowerment and community engagement (15). It upholds a holistic and proactive approach to health and well-being and can serve as a basis for health system strengthening.

Primary health care-oriented health policies and plans can enhance equity through context-specific strategies that focus on reaching groups that experience disadvantage and stand to benefit from policies to increase health service access and financial protection (16). This has been achieved through means such as:

prioritizing public funding and explicit coverage of essential health services for groups experiencing disadvantage;

allocating defined communities to specific health teams that can provide care holistically through the process of empanelment;

developing decentralized multidisciplinary teams that include community health workers and managers;

making care more approachable and acceptable through community-led approaches;

using technologies to bring care to underserved areas.

The 2020 WHO Operational framework for primary health care proposed a set of 14 strategic and operations levers, with corresponding actions and interventions for national, subnational and community stakeholders to advance equity-oriented primary health care policies (17). The monitoring and evaluation lever recognizes the importance of using data and information to support the continuous processes of prioritization, decision-making and planning that are inherent to strengthening primary health care. To this end, countries require comprehensive, coherent and integrated approaches to monitoring and evaluation that encompass a broad set of health indicators and inequality dimensions. In 2022, WHO released a primary health-care measurement framework. This included a menu of indicators for policy-makers and leaders to track and monitor progress in strengthening primary health care-oriented health systems as a key proponent of accelerating universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The guidance recommends that monitoring includes data disaggregated by diverse dimensions of inequality relevant to the indicator and context (18).

Universal health coverage

Achieving universal health coverage – which is the aim of SDG target 3.8 – means that all people have access to the full range of good-quality health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship. This covers the full continuum of essential health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care across the life course (19). Health inequality monitoring and equity-oriented target-setting can support the realization of universal health coverage (20).

Policies can support universal health coverage by ensuring health services are used relative to need; are efficiently delivered and accessed; are of good quality; and are offered in an environment of transparency and accountability. The expansion of universal health coverage requires policy action on three fronts: expanding the number and extent of services that are covered; expanding coverage to people who are not covered; and protecting people from the financial consequences of paying out of pocket when they seek health services. Given this complexity, universal health coverage cannot be attained all at once and by using a singular approach or strategy – rather, it requires progressive universalism.

Progressive universalism

The concept of progressive universalism is central to promoting equity throughout the process of advancing universal health coverage (21). As health services are expanded as part of universal health coverage, fair progressive universalism approaches require that services be allocated according to need, such that people with greater needs receive more services (22). In this way, the advancement of universal health coverage intentionally provides services to population subgroups experiencing disadvantage first, rather than providing services to everyone and assuming it reaches those in greatest need (sometimes called a “trickle-down approach”).

Progressive universalism is an approach to reaching universal health coverage that ensures disadvantaged populations realize equal or greater gains until the goal of universalism is eventually approached (23).

A general strategy for countries seeking fair progressive realization of universal health coverage requires:

categorizing health services into priority classes, using criteria related to cost-effectiveness, prioritizing people who are worse off, and financial risk protection;

expanding coverage for high-priority services to everyone, including financial protection and sustainable financing mechanisms;

ensuring groups experiencing disadvantage are not left behind (21).

Progressive universalism requires the approach of advancing service coverage in an incremental fashion. An aspirational essential set of services can be defined, and then a core set of services within this can first be provided to all people. Once the budget and system resources allow, the scope of services can be increased over time (24). Progressive universalism also requires that healthy and wealthy members of society cross-subsidize people who experience ill-health, vulnerability, poverty or other forms of disadvantage, through the exercise of social solidarity (22). Although there may be competing considerations when pursuing the fair, progressive realization of universal health coverage, certain trade-offs have been identified as inequitable and therefore unacceptable (Box 8.2).

BOX 8.2. Unacceptable trade-offs for the fair progressive realization of universal health coverage

The following compromises are considered unacceptable when pursing the fair progressive realization of universal health coverage:

It is unacceptable to expand coverage for low- or medium-priority services before achieving near-universal coverage for high-priority services. This includes reducing out-of-pocket payments for low- or medium-priority services before eliminating out-of-pocket payments for high-priority services.

It is unacceptable to prioritize very costly services whose coverage will provide substantial financial protection when the health benefits are very small compared with alternative, less costly services.

It is unacceptable to expand coverage for more-advantaged groups before doing so for less-advantaged groups, when the costs and benefits are similar. This includes expanding coverage for people with already high coverage before groups with lower coverage.

It is unacceptable to give priority to people with the ability to pay and to not include informal workers and poor people, even if such an approach would be easier.

It is unacceptable to shift from out-of-pocket payments towards mandatory prepayments in a way that makes the financing system less progressive (21).

Equity-oriented policies are central to the realization of universal health coverage through progressive universalism. There are, however, some challenges. Disadvantaged populations may be difficult to identify and reach through programming, underscoring the need to establish strong health inequality monitoring systems alongside effective equity-oriented service delivery platforms. There may be challenges with regard to health system capacity in priority communities. Dedicated efforts may be required to achieve effective coverage, defined as “the proportion of people in need of services who receive services of sufficient quality to obtain potential health gains” (25). For more on the assessing effective coverage and the Tanahashi framework, see Box 8.3.

BOX 8.3. Tanahashi framework for assessing service coverage

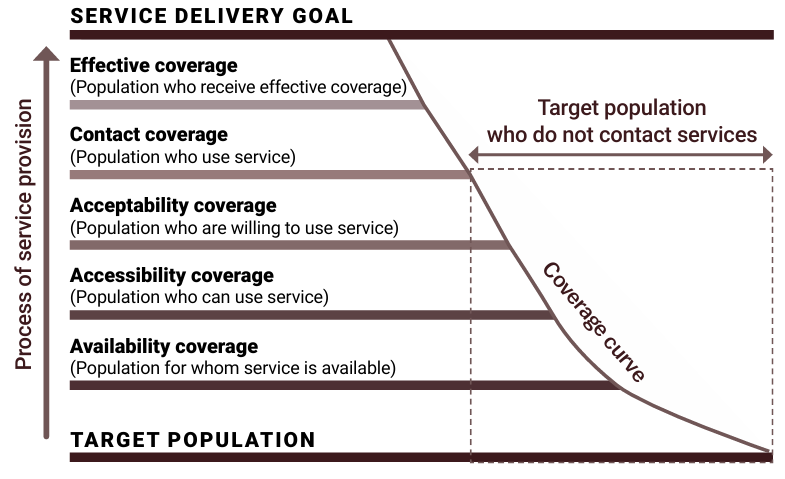

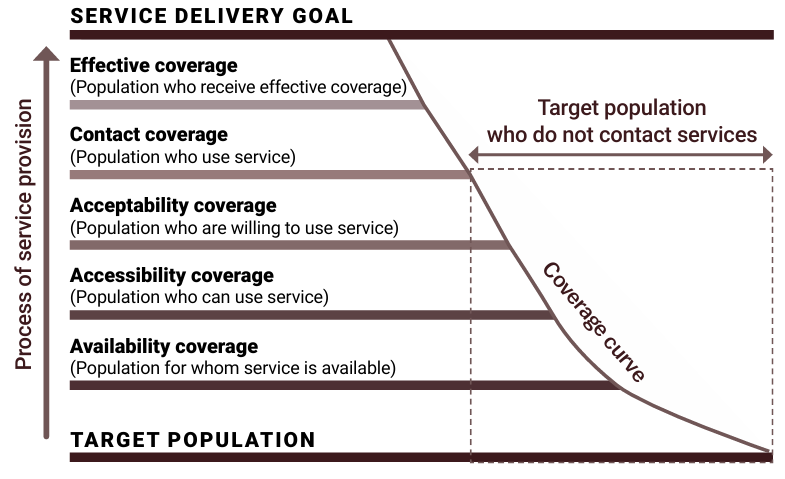

The Tanahashi framework can be used to identify, map and monitor gaps and barriers along a coverage continuum. The framework illustrates coverage of a given service or group of services (e.g. a benefits package) as a cascade Figure 8.1. The cascade begins with availability coverage, representing what services are being provided, where and by whom. Following this, it captures the extent to which such services are within reasonable reach (accessibility coverage). Even if services are available and accessible, users may not be willing or able to use these services because they are not affordable or culturally appropriate (acceptability coverage). Next on the cascade is contact coverage, representing the extent to which services are being used – although this may not mean that the services are effective. Effective coverage is the extent to which services are safe, of good quality, efficient, and found to be satisfactory by users (26).

FIGURE 8.1. Tanahashi framework of coverage

Using data disaggregated by relevant inequality dimensions, the Tanahashi framework can be used as a basis to explore inequalities in levels of attainment of service coverage, leading to deeper understanding of the different barriers to effective coverage and entry points for equity-oriented policy responses. According to a 2023 review, applications of the Tanahashi framework across different settings and health topics frequently reveal a large drop in effective coverage across the processes of service provision (28).

The Tanahashi framework was used as part of a barriers assessment activity in the Republic of Moldova in 2011. The assessment found that many gaps in health service coverage remained. Furthermore, there was a lack of routine monitoring of effective coverage and scant information about populations that are excluded or experiencing disadvantage. The report made several recommendations for policy and research to address gaps across each level of the cascade (29).

The WHO Handbook for conducting assessments of barriers to effective coverage with health services elaborates more on methods for exploring barriers and facilitating factors to effective coverage within each of the coverage domains of the Tanahashi framework. It contains additional examples of how the framework has been used to inform policy and programming (27).

Priority public health conditions analysis framework

Designing policies to tackle health inequities requires a deep understanding of how inequities are generated, which can then inform supportive policy environments to address and mitigate them. The priority public health conditions analysis framework provides a practical and holistic approach for analysing, intervening and measuring health equity and its determinants across five levels of analysis, spanning:

structure of society, encompassing socioeconomic contexts, relations and positions;

differential environmental exposures through social and physical environments;

differential vulnerability resulting from population characteristics;

differential health outcomes across individuals;

differential consequences of poor health.

At each level, analyses are aimed at establishing entry points for interventions and understanding potential side-effects, sources of resistance to change, and lessons learnt from previous experiences (30). The components of the framework reflect the social origins of health inequities proposed by Diderichsen and colleagues (31) and applied in the work of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health Priority Public Health Knowledge Network (30). The framework aligns with the political commitments expressed in the 2011 Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health (Box 8.4). For more on social determinants of health, see Chapter 9.

BOX 8.4: Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health

The 2011 Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health expresses global political commitments to “achieve social and health equity through action on social determinants of health and well-being by a comprehensive intersectoral approach” (32). The declaration identified five key action areas for advancing health equity: adopting better governance for health and development; promoting participation in policy-making and implementation; further reorienting the health sector towards reducing health inequities; strengthening global governance and collaboration; and monitoring progress and increasing accountability.

The priority public health conditions analysis framework has been widely applied. For example, it was used to understand the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 across ethnic minority groups and Indigenous Peoples. The analysis elucidated key drivers of the greater risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 among ethnic minority groups and Indigenous Peoples, and the differential vulnerability, exposure, and consequences experienced by ethnic minority groups and Indigenous Peoples. Opportunities for interventions to address racism, racial discrimination and intersecting drivers of inequity in service coverage were identified (33).

References

1. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1946 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/121457, accessed 4 September 2024).

2. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2015 (https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf, accessed 27 June 2024).

3. Developing national institutional capacity for evidence-informed policy-making for health. Cairo: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2019 (https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/RC_Technical_Papers_2019_6_en.pdf, accessed 4 September 2024).

4. Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:27106. doi:10.3402/gha.v8.27106.

5. Sandiford P, Vivas Consuelo D, Rouse P, Bramley D. The trade-off between equity and efficiency in population health gain: making it real. Soc Sci Med. 2018;212:136–144. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.005.

6. Culyer AJ. The bogus conflict between efficiency and vertical equity. Health Econ. 2006;15:1155–1158. doi:10.1002/hec.1158.

7. Country planning cycles. Geneva: World Health Organization (https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/planning-cycle, accessed 4 September 2024).

8. Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(2):190–193. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-201257.

9. Mantoura P, Morrison V. Policy approaches to reducing health inequalities. Montreal: National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy; 2016 (https://www.ncchpp.ca/docs/2016_Ineg_Ineq_ApprochesPPInegalites_En.pdf, accessed 4 September 2024).

10. World Health Assembly Resolution 30.43. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1977 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/86036, accessed 19 September 2024).

11. Primary health care: report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. Alma-Ata: World Health Organization; 1978 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/39228, accessed 23 September 2024).

12. Kickbusch I. The contribution of the World Health Organization to a new public health and health promotion. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):383–388. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.3.383.

13. Declaration of Astana: Global Conference on Primary Health Care: Astana, Kazakhstan, 25 and 26 October 2018. Astana: World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund; 2018 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/328123, accessed 23 September 2024).

14. Draft fourteenth general programme of work, 2025–2028. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 (https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA77/A77_16-en.pdf, accessed 18 June 2024).

15. Rajan D, Rouleau K, Winkelmann J, Kringos D, Jakab M, Khalid F, editors. Implementing the primary health care approach: a primer. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376777, accessed 19 September 2024).

16. Ruano AL, Wong B, Winkelmann J, Saksena P, Gaitan-Rossi P. The impact of PHC on equity, access and financial protection. In: Rajan D, Rouleau K, Winkelmann J, Jakab M, Kringos D, Khalid F, editors. Implementing the primary health care approach: a primer. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376777, accessed 19 September 2024).

17. Operational framework for primary health care: transforming vision into action. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund; 2020 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/337641, accessed 4 September 2024).

18. Primary health care measurement framework and indicators: monitoring health systems through a primary health care lens. Geneva: World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund; 2022 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/352205, accessed 4 September 2024).

19. Universal health coverage (UHC). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc), accessed 23 May 2024).

20. Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Koller T, Prasad A, Schlotheuber A, Valentine N, et al. Equity-oriented monitoring in the context of universal health coverage. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001727. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001727.

21. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage: final report of the WHO consultative group on equity and universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/112671, accessed 23 September 2024).

22. Sen G, Govender V, El-Gamal S. Universal health coverage, gender equality and social protection: a health systems approach. New York: UN Women; 2020 (https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/25216112/38, accessed 4 September 2024).

23. Gwatkin DR, Ergo A. Universal health coverage: friend or foe of health equity? Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2160–2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62058-2.

24. Rao KD, Makimoto S, Peters M, Leung GM, Bloom G, Katsuma Y. Vulnerable populations and universal health coverage. In: Kharas H, McArthur JW, Ohno I, editors. Leave no one behind: time for specifics on the sustainable development goals. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2020 (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/LNOB_Chapter7.pdf, accessed 4 September 2024).

25. Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the Sustainable Development Goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e152–e168. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30472-2.

26. Tanahashi T. Health service coverage and its evaluation. Bull World Health Organ. 1978;56(2):295.

27. Handbook for conducting assessments of barriers to effective coverage with health services: in support of equity-oriented reforms towards universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/377956, accessed 23 September 2024).

28. Karim A, de Savigny D. Effective Coverage in health systems: evolution of a concept. Diseases. 2023;11(1):35. doi:10.3390/diseases11010035.

29. Barriers and facilitating factors in access to health services in the Republic of Moldova. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/375372, accessed 23 September 2024).

30. Blas E, Sivasankara Kurup A. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44289, accessed 2 July 2024).

31. Diderichsen F, Evans T, Whitehead M. The social basis of disparities in health. In: Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M, editors. Challenging inequities in health: from ethics to action. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

32. Rio Political Declaration on the Social Determinants of Health. Rio de Janeiro: World Health Organization; 2011 (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/rio-political-declaration-on-social-determinants-of-health, accessed 8 July 2024).

33. Irizar P, Pan D, Taylor H, Martin CA, Katikireddi SV, Kannangarage NW, et al. Disproportionate infection, hospitalisation and death from COVID-19 in ethnic minority groups and Indigenous Peoples: an application of the Priority Public Health Conditions analytical framework. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;68:102360. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102360.