Chapter 2. Approaches to health inequality monitoring

Overview

Monitoring health inequalities provides evidence on who is being left behind, with the purpose of informing equity-oriented health policies, programmes and practices. Varied approaches to monitoring draw from different types of information, yielding complementary forms of evidence that together inform a more holistic view on the state of health inequality than any one approach in isolation.

The objective of this chapter is to introduce attributes of the approach to within-country inequality monitoring that is the primary focus of the book by explaining how it is distinct from complementary approaches. The chapter begins by differentiating between qualitative and quantitative approaches to exploring health inequalities, and then contrasts measures of between-country and within-country inequality. Finally, a five-step cycle of inequality monitoring is described, offering a framework for conducting within-country health inequality monitoring.

Qualitative and quantitative explorations of health inequality

Health inequalities can be assessed using qualitative and quantitative methods, which offer distinct and complementary perspectives. Qualitative approaches tend to explore the nature of inequalities and their drivers through non-numerical data derived from document study, observations, interviews and focus groups. Qualitative approaches can provide rich information about how inequalities are experienced and help to guide policy recommendations that reflect how people live their lives. The findings of qualitative studies are particularly useful to illustrate what is or is not working well in a specific context; give information about the accessibility, affordability and equitability of services; and provide insight on opportunities for intervention.

Quantitative approaches rely on numerical data and statistical analysis techniques to measure and quantify inequalities in health. Using data derived from sources such as surveys, censuses, statistical records and registers, quantitative methods facilitate comparisons of inequalities between populations and evaluation of trends over time.

Parts 3 and 4 of this book are primarily focused on guidance for quantitative methods of assessing health inequalities, but qualitative approaches are also part of health inequality monitoring. For example, a priori qualitative analysis is important to guide the selection of relevant indicators and dimensions of inequality (see Chapter 3). The integration of both qualitative and quantitative approaches is needed to form a comprehensive and well-rounded understanding of health inequalities and their implications for equity-oriented decision-making (see Chapter 24).

Between-country versus within-country inequality

Between-country and within-country inequality are two distinct ways of measuring health inequalities, each reflecting a different scope of monitoring. Measures of between-country inequality consider differences across two or more countries, providing insights into regional or global trends. Such comparisons may be based on a health indicator measurement or a socioeconomic measurement, such as gross national income per capita or multidimensional vulnerability index.

The United Nations multidimensional vulnerability index was created as a complement to gross national income to measure structural vulnerability and lack of resilience across multiple dimensions of sustainable development at the national level (1).

Between-country inequality may entail comparisons between single countries – for example, how does a health indicator measurement in one country compare with the measurement in another country? It may also entail comparisons between defined groups of countries that share a common characteristic – for example, comparing a health indicator in low-income and high-income countries. Measures of within-country inequality consider differences across two or more subgroups of a national or subnational population. This approach to monitoring reveals inequality trends within countries and is the predominant approach to monitoring inequalities addressed in this book.

Between-country and within-country inequality measurements are not mutually exclusive. Comparisons of within-country inequality can be made between countries (Box 2.1). For more discussion about the purpose and contributions of health inequality monitoring across global, regional, national and subnational contexts, See Chapter 4.

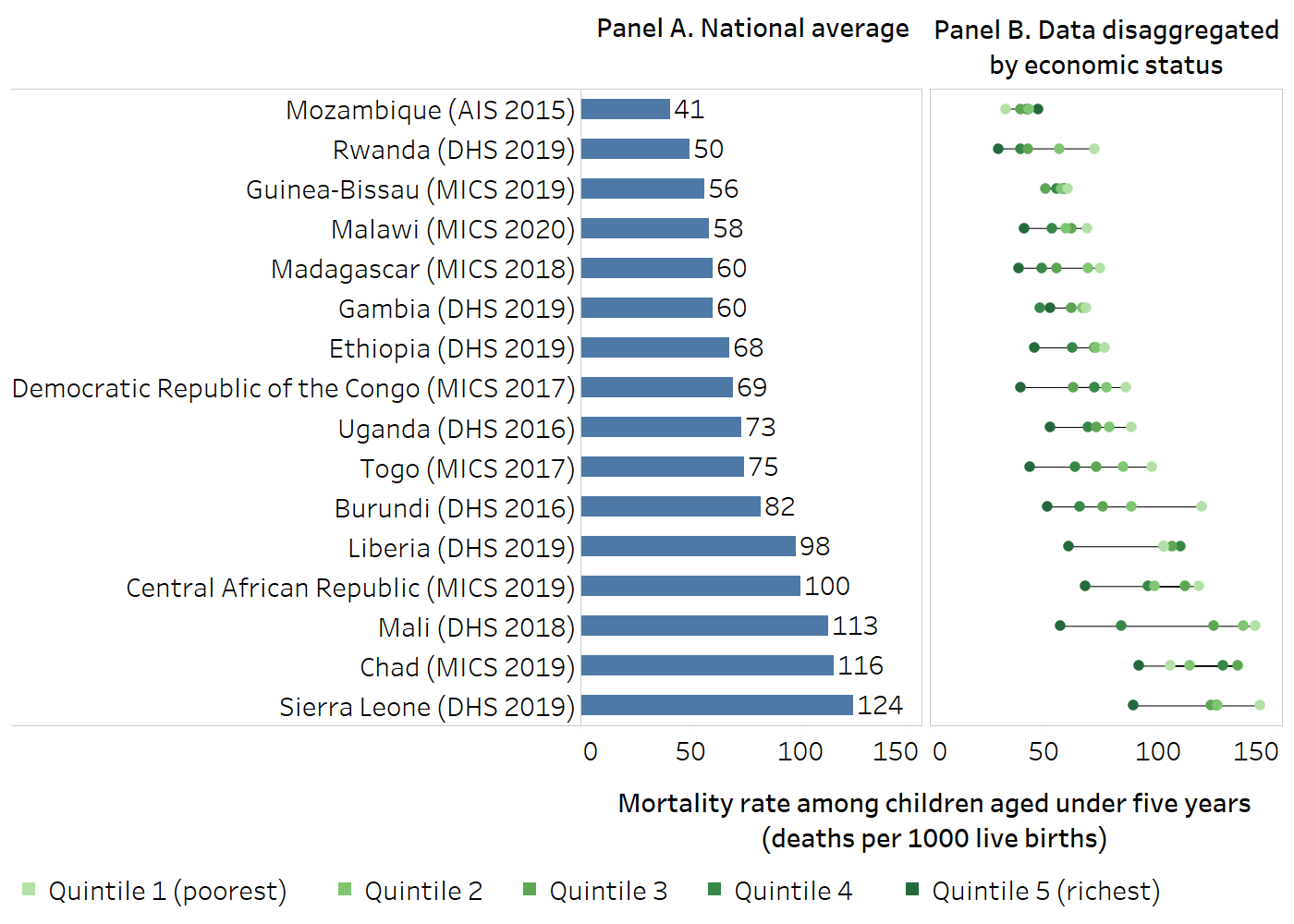

BOX 2.1. Between-country and within-country inequalities: mortality among children aged under five years, low-income African countries

The following example draws on household survey data about mortality among children aged under five years in 16 low-income countries in the WHO African Region (Figure 2.1). Panel A shows the national average under-five mortality rate for the 16 countries, demonstrating between-country inequality. Of the countries with available data between 2015 and 2020, Mozambique had the lowest national average rate of under-five mortality and Sierra Leone had the highest.

Panel B contains data on under-five mortality for wealth quintiles in each country, showing within-country economic-related inequality. The extent of within-country inequality is indicated by the length of the horizontal line connecting the two dots representing the quintiles with the highest and lowest mortality. A between-country comparison of within-country inequality could conclude that economic-related inequality was the narrowest in Guinea-Bissau and the widest in Mali.

FIGURE 2.1. Mortality rate among children aged under five years (deaths per 1000 live births), 16 low-income countries in the WHO African Region

AIS, AIDS Indicator Survey; DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

Horizontal lines show the range between the lowest and highest subgroup estimates for each country.

Source: derived from the WHO Health Inequality Data Repository Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health dataset (2), with data sourced from the most recent AIS, DHS or MICS between 2015 and 2020.

Five-step cycle of inequality monitoring

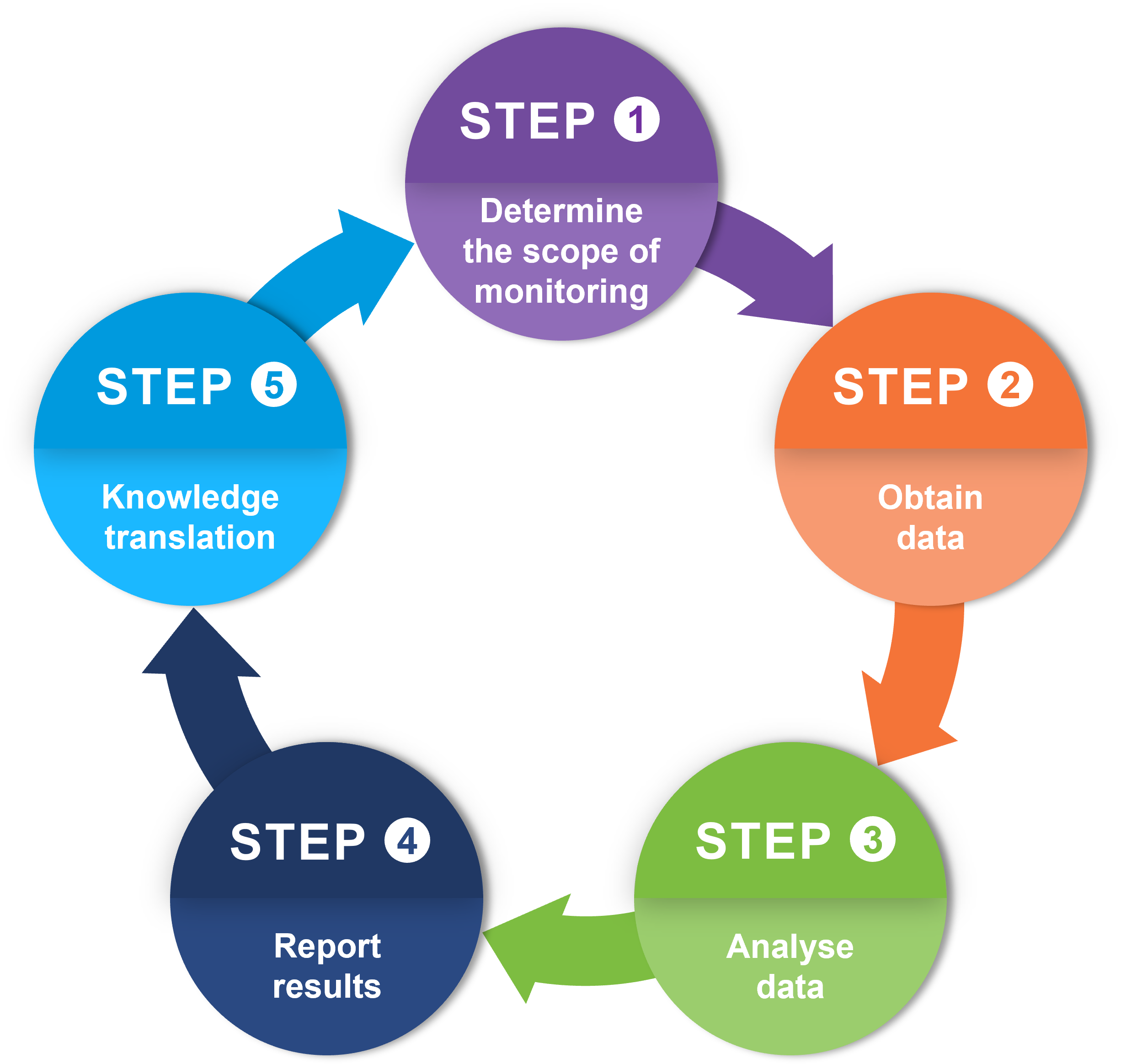

This book focuses on the assessment of within-country health inequality. To this end, a five-step cycle of health inequality monitoring provides a simplified depiction of the process (Figure 2.2). The cycle begins with determining the scope of monitoring (Step 1) and obtaining the data (Step 2). The data are analysed (Step 3), and the results are reported to relevant target audiences (Step 4). Step 5 addresses knowledge translation, facilitating the uptake of monitoring results to inform changes. To continue to monitor the effects of these changes, more data must be collected that describe the ongoing health of the population. Thus, the cycle of monitoring is continuous. This five-step cycle of health inequality monitoring can be applied across any health topic and population (Box 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2. Five-step cycle of health inequality monitoring

BOX 2.2. Step-by-step manuals for health inequality monitoring

WHO has a series of step-by-step manuals and workbooks that aim to build capacity for implementing the five-step cycle of monitoring. National health inequality monitoring: a step-by-step manual provides general guidance on the application of the cycle within national contexts (3). Subsequent versions of the Manual contextualize the steps within the topics of immunization (4) and sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (5). The health inequality monitoring workbooks contain exercises that facilitate the application of the five steps (6, 7). The step-by-step process of health inequality monitoring is further supported through a series of eLearning courses (8).

Step 1: determine the scope of monitoring

Step 1 establishes the general purpose and scope of the monitoring exercise. This step entails putting in place the parameters that guide the subsequent steps of monitoring. Step 1 is broken down into three sub-steps, which can be approached concurrently, guided by the overarching purpose of monitoring and with consideration of existing priorities and resources.

Step 1A asks the key question: which health topic and population (or populations) will the monitoring activity encompass? Populations (groups of people) are often defined based on geographical or administrative boundaries – global, regional, national, provincial, district, municipal and so on. Monitoring should ideally encompass all members of the affected population within the area, through whole-population or representative sampling.

Step 1B – identify relevant health indicators – looks at which range of health indicators is best suited to inequality monitoring. In selecting health indicators for monitoring inequality, an initial consideration is the desired breadth of the health topic. Will the topic be narrowly defined, and therefore include indicators that are directly linked with that topic? Or will a broad lens be adopted, incorporating a wider selection of health indicators across aspects of the health sector and other health-related indicators?

Step 1C considers relevant dimensions of inequality. Dimensions of inequality are the categorizations on which subgroups are formed for inequality monitoring. They generally reflect sources of discrimination or social exclusion that negatively impact health, including social, economic, demographic and geographical factors. Applying a single dimension of inequality may not always be sufficient to meaningfully capture inequality within a population. Double disaggregation involves applying two dimensions of inequality simultaneously, while multiple disaggregation applies more than two dimensions.

Chapter 3 includes more information on the selection of health topics and indicators and dimensions of inequality.

Step 2: obtain data

Step 2 obtains two streams of data: data about health indicators and data about dimensions of inequality. Step 2A involves mapping data sources – a systematic approach to assessing which sources contain data about relevant health indicators and dimensions of inequality (see Chapter 15). The results of this mapping exercise indicate whether data are available to proceed with inequality monitoring, a determination that is made in Step 2B. In some situations, there may be multiple sources that contain relevant data. Weighing the strengths and limitations of the different options can help in deciding which source to use. If data are limited, non-representative, unavailable or of poor quality, other action will be needed to reassess the scope of monitoring (returning to Step 1) or to advocate for expanded or improved data collection. Data sources for health inequality monitoring are discussed in more detail in Part 2.

Step 3: analyse data

Step 3 generates numerical descriptions of the patterns and magnitude of inequality. Preparing disaggregated data is the first sub-step of data analysis, Step 3A (see Chapter 17). Disaggregated data can be inspected to get an initial sense of patterns in the data across the population subgroups, which are defined by dimensions of inequality.

In Step 3B, summary measures of health inequality are calculated to concisely represent the level of inequality across subgroups. There are numerous summary measures of health inequality, ranging from simple pairwise measures that compare two subgroups, to complex measures that take into account data from multiple subgroups. More information about health data disaggregation and summary measures of health inequality can be found in (Part 4).

Step 4: report results

Reporting reflects aspects of all the previous steps of the inequality monitoring cycle, conveying information about the overarching purpose and scope of monitoring, the data sources and the key results. Reporting activities should begin with a thorough understanding of the results from the data analysis. Interpreting results, identifying key findings, and deriving conclusions and recommendations are iterative and often collaborative processes. They rely on a solid understanding of the technical aspects of analysis and broad knowledge about the population, context and target audience.

Reporting the results of health inequality analyses can be approached through five sub-steps. First, the specifics of reporting should be guided by a specific purpose (goals and objectives) and target audience for the reporting activity: defining these aspects of reporting is Step 4A. Multiple reporting outputs may be prepared with different purposes and audiences in mind. Once these parameters are established for a specific reporting output, the scope of reporting (Step 4B), the technical content (Step 4C) and the methods of data presentation (Step 4D) can be determined. Finally, reporting outputs should adhere to high standards of reporting, containing all the necessary technical and nontechnical information to contextualize the main messages, recommendations and conclusions (Step 4E). See Chapters 7 and 23 for more about reporting as part of health inequality monitoring.

Step 5: knowledge translation

Step 5 pertains to knowledge translation. Knowledge translation is the synthesis, exchange and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health. Ideally, multiple forms of knowledge and evidence – including qualitative and quantitative studies, lived experiences, programme and policy expertise, and practitioner perspectives – should be considered alongside the results of inequality monitoring.

When knowledge translation happens effectively, the evidence generated from health inequality monitoring is taken up to effect change and achieve greater equity. Monitoring is then poised to continue from the first step, adapting to new circumstances and evolving situations. For more information on knowledge translation, see Part 2 and Chapter 24.

References

1. High-level panel on the development of a multidimensional vulnerability index: final report. New York: United Nations; 2024 (https://www.un.org/ohrlls/mvi, accessed 23 September 2024).

2. Health Inequality Data Repository. Geneva: World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/data/inequality-monitor/data, accessed 20 June 2024).

3. National health inequality monitoring: a step-by-step manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/255652, accessed 23 September 2024).

4. Inequality monitoring in immunization: a step-by-step manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/329535, accessed 23 September 2024).

5. Inequality monitoring in sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, 1 child and adolescent health: a step-by-step manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/351192, accessed 23 September 2024).

6. Health inequality monitoring workbook: exercises to guide the process of health inequality monitoring, 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/375740, accessed 23 September 2024).

7. Companion workbook: exercises to guide the process of inequality monitoring in sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 (https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/351403, accessed 23 September 2024).

8. Training. Geneva: World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/data/inequality-monitor/training, accessed 4 September 2024).